In 16th year of his majesty when Emperor Qianlong’s mother had her 60th birthday, the emperor, who claimed to be ruling his country by giving moral example of filial obedience, had a new monastery built for his mother at the site of former Jingyuan Temple, at the west outskirt of Beijing. He named his birthday present the Grand Grace and Longevity Temple. In 16th year of his majesty when Emperor Qianlong’s mother had her 60th birthday, the emperor, who claimed to be ruling his country by giving moral example of filial obedience, had a new monastery built for his mother at the site of former Jingyuan Temple, at the west outskirt of Beijing. He named his birthday present the Grand Grace and Longevity Temple.

He also decreed that Wengshan Hill shall be named longevity Hill and West Lake be named kunming Lake. The emperor intended to build another garden too, which he’d call Qingyi Garden. But the project could be very costly.

In order to get his ambition fulfilled without arousing the objection of ministers and the people, the emperor decided to launch the extensive water supply project which would then include the expansion of the royal gardens as well as waterway dredging and reservoir improvement. Royal gardens such as Yuanming Yuan and Changchun Yuan had been dependent on Yuquan Hill and West Lake for water supply.

Yuquan hill spring was the major water resource of the imperial households in the Forbidden City and the origin of the canal Tonghui River. Too much water consumption at the upper stream would result in water shortage in the imperial palaces and in the inland navigation difficulty as well. Emperor Qianglong intended to kill two birds with one stone in his West Beijing project.

So the project began in the 14th year of Emperor Qianlong. Waterways leading from Yuquan Hill and West Hill were dredged up, West Lake was dug deeper, and water gates were installed. And Qingyi Garden was also under construction in this comprehensive undertaking, which was expected to benefit the people and celebrate the birthday of the emperor’s mother.

But there was consideration other than luxury in construction of imperial residences at the west outskirts of the capital, the consideration of safety. The Manchu rulers deployed their royal guards out in the rural areas northwest of the city when they took Beijing so that they felt safe when surrounded by the subjugated han nationality in the Forbidden City.

But there was consideration other than luxury in construction of imperial residences at the west outskirts of the capital, the consideration of safety. The Manchu rulers deployed their royal guards out in the rural areas northwest of the city when they took Beijing so that they felt safe when surrounded by the subjugated han nationality in the Forbidden City.

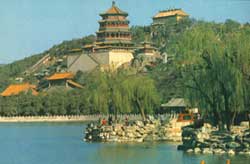

The Garden was completed in the 20th year of Emperor qianlong. The emperor was delighted and composed a lyric to celebrate his new garden, “Relax in the Mountain and enjoy a break, with the unrivalled landscape by the Lake.” To be fair with the emperor, his project was a fine combination of gardening with water resource improvement though the imperial households were not to enjoy this for long.

In 1860 the Anglo-French Allies took Beijing and looted and set fire on imperial gardens including Yiqing Garden. The Hall of Foxiangge on top of the hill was burned to the ground. Thirty years later, on February 1st 1888, Emperor Guangxu changed the garden’s name into Yiheyuan in celebrating the 60th birthday of his mother, Empress Dowager Ci Xi.

In his decree of re-designation the emperor expressed a son’s affection for his mother, presenting the renovated garden to her so that she, who was about to relinquish the sovereignty to the emperor, would have a place to enjoy her late years. The name Yiheyuan, nowadays better known as the Summer Palace, means joy and peace for the elderly. By the time the order was issued the renovation had been in process for 16 months.

But the decree, as most of the decrees issued by name of his majesty, was actually made by the Empress Dowager herself, who hypocritically admonished his son to be sparing with the revenue and be a good emperor. Whereas the empire was in its robust prime when Yiqing Garden was built, Emperor Guangxu, 130 years later, found his country in a critical situation with crises both from home and abroad and a weakening economy. The empress, who was not unmindful that his son’s annual revenue would not be enough for the construction, left aside the construction Ministry and the Office of Royal Gardening and entrusted the construction with the Royal Navy, one of the fruits of “foreign entrepreneurialism movement”.

Leaders of the Naval department understood what her majesty meant and appropriated funds for the navy in the construction. And in order to make the funding appear legal Empress Dowager Ci Xi ordered the modern navy drill to be resumed in Kunming Lake and founded a naval academy in the garden.

The emperor insisted that the construction was a humble present from a grateful son. The naval minister, the emperor’s father, said reassuringly that the garden, where the inspection of navy parade was to take place would be used for her majesty’s birthday ceremony as well. Both of them had other purposes in mind. The father wanted to move the empress dowager out of the palace so that his son would be able to assume the power; the son desired to rid himself of his step mother who had been in the way of his reformation. They were both disappointed.

The emperor insisted that the construction was a humble present from a grateful son. The naval minister, the emperor’s father, said reassuringly that the garden, where the inspection of navy parade was to take place would be used for her majesty’s birthday ceremony as well. Both of them had other purposes in mind. The father wanted to move the empress dowager out of the palace so that his son would be able to assume the power; the son desired to rid himself of his step mother who had been in the way of his reformation. They were both disappointed.

When the garden was completed Empress Dowager Ci Xi took residence here with the emperor and went on meeting ministers and delegating business while she “enjoyed her late years”. She didn’t return to the Forbidden City until late that year.

In 1894 navies of China and Japan clashed on Yellow Sea. The battle ended with a miserable failure of Chinese Empire, which proved the sparkle of the reform supported by Emperor Guangxu.

In the 23rd day of the fourth moon, 24th year of his majesty, Emperor Guangxu, who had by then assumed the office, issued the reform decree, which initiated a number of renovating measures.

One hundred days later, however, Empress Dowager Ci Xi forced the emperor to take his decree back and invite her once again to take the power. The short-lived reform policy ended with execution and exile of the leading reformists and the house arrest of the emperor himself in the Hall of Jade Billows of the Summer Palace. The empress had the hall surrounded with walls and deployed guards at the entrances. The premises were as fast secured as a prison.

Sections of the walls around the hall still can be seen today. The wall is within the gate less than one metre apart so that it easily escapes one’s notice from outside. The wall on the east prevented the emperor from getting to the Hall of Benevolence and Longevity to be informed with current affairs, and the wall on the west cut off his escape from the lake. Splendid architecture disguised the traps of political struggle and conspiracy.

A close review of the history of gardening reveals that most of Chinese imperial gardens were built around the 100th anniversary of a dynasty. Construction of royal gardens of splendor requires a sound economy which a new government cannot achieve at once, all its resources going to safeguarding the newly established sovereignty against any possible threat. The first rulers of a dynasty always gave priority to the symbolic architectures of their reigns and delayed constructions of villas and imperial gardens till the economy recovered well enough. It went this way with little exception throughout the history. Qingyi Garden, for example, was built in the 15th year of Emperor qianlong, 106 years after the qing Dynasty was founded.

A close review of the history of gardening reveals that most of Chinese imperial gardens were built around the 100th anniversary of a dynasty. Construction of royal gardens of splendor requires a sound economy which a new government cannot achieve at once, all its resources going to safeguarding the newly established sovereignty against any possible threat. The first rulers of a dynasty always gave priority to the symbolic architectures of their reigns and delayed constructions of villas and imperial gardens till the economy recovered well enough. It went this way with little exception throughout the history. Qingyi Garden, for example, was built in the 15th year of Emperor qianlong, 106 years after the qing Dynasty was founded.

In Chinese classic gardening, the contractors, those who paid for the construction and those who came up with the design, determined what a garden should be like. The architects were only agents, putting into effect what was in the contractor’s mind. In the 16th year of his majesty, Emperor Qianlong made his first visit to South China in an attempt to win the loyalty of the han gentlemen there. The nomadic lord was fascinated with the beauty of the south and had the landscape portrayed for his gallery.

Emperor Qianlong, an enthusiastic traveler, visited South China six times during his reign, his visit tour covering such major cities as Yangzhou, Suzhou, Hangzhou, Wuxi and Haining, where he had the private gardens of best design copied for his own gardens back in Beijing. Qingyi Garden was an imitation of South China gardening. And Kinming Lake, with the hills around it, the isles and the architectures on it, is just the West Lake in Hangzhou in miniature. The six bridges at the West Shore are copies of the Sudi Six Bridges in Hangzhou; the northwest part of the lake, the Long Island and the bridges there remind a visitor of the Minor West Lake in Yangzhou; and the Garden of Joy is obviously a duplicate of Jichang Garden in Wuxi. The visitor has the impression that he is visiting South China gardens. Apart from landscapes of this world, he will also see fairy land in this imperial garden.

The South Lake Isle on the lake together with the Hall of zhijingge and Jianzaotang makes a typical three-hill-one-lake gardening arrangement, a reference to the fairyland in mythology. And the architectural features of Wangchange, Hall of Moon Light on the isle and the 17-Arch Bridge imitate the Palace of the legendary Moon Goddess.

Both the realistic architecture and the imaginary landscapes represent the grandeur of the emperor, ruler and landlord of the whole nation.

Emperors of Qing Dynasty adopted Confucianism as the orthodox philosophy. This canonization can also be seen in the architecture of Qingyi Garden and the Summer Palace.

Emperor Qianlong, who built the Grand Grace Longevity Temple and who changed the name of Wengshan Hill into Longevity Hill for his mother’s 60th birthday, gave an example of the voluntary adoption of the advanced moral philosophy by an intrusive tribe.

Emperor Qianlong, who built the Grand Grace Longevity Temple and who changed the name of Wengshan Hill into Longevity Hill for his mother’s 60th birthday, gave an example of the voluntary adoption of the advanced moral philosophy by an intrusive tribe.

His example was copied by Emperor Guangxu, who rebuilt the Summer Palace at the site of Qingyi Garden for his stepmother Empress Dowager Ci Xi.

The imperial garden also represents the Confucian hierarchy in the arrangement of office complex, bedrooms and backyards.

The office complex, which centres upon the Hall of Benevolence and Longevity, gives a sense of solemnity by virtue of the ever narrowed front yards and the ever higher buildings as one enters the premises layer by layer. The bronze incense burner and bronze lions in front of the centre hall are a constant reminder of the rigid hierarchy of the Forbidden City.

The Hall of Happiness and Longevity for the empress dowager, the Hall of Jade Billows for the emperor and the Hall of Yiyunguan for the queen comprise the private palaces of the imperial household. The palace of the empress dowager, who was of course the most venerated, sits in the north and faces the south. The emperor and the queen, accompanying their mother, had their houses on the east and west side of the central palace. And the queen’s palace is smaller than the emperor’s. Everything is arranged according to the family and social hierarchy, which finds justification in Confucianism.

Buddhist temples were also built in the summer Palace, indicating the religious inclination of the Qing Rulers.

Qingyi Garden housed 11 monasteries. The Grand Grace Longevity Temple, Emperor Qianlong’s birthday present for his mother, was the major one in the Buddhist complex. The emperor had also wanted to erect a pagoda on top of the hill following the example of Grace Temple in Nanjing and the Liuhe Pagoda in Huangzhou.

Qingyi Garden housed 11 monasteries. The Grand Grace Longevity Temple, Emperor Qianlong’s birthday present for his mother, was the major one in the Buddhist complex. The emperor had also wanted to erect a pagoda on top of the hill following the example of Grace Temple in Nanjing and the Liuhe Pagoda in Huangzhou.

The unfinished pagoda collapsed when the 8th story was completed. A geomancer insisted that it was not advisable to build pagoda at the northwest outskirts of Beijing. The emperor then had a wood octagon hall erected here instead. It is known as the Foxiangge today. The hall is much more beautiful and in harmony with the landscape than the pagoda would have been. The radially symmetrical tower looked exactly the same when viewed from all directions. It became the soul of the Summer Palace and of the so- called three-hill-five-garden palace complex.

In accordance with a liberal religious policy, the empire was conciliatory with the Mongolians and the Tibetans, most of them Tibetan Buddhists. Lama temples were given a prominent place in the Summer Palace among architectures of han tradition.

Apart form Buddhism traces of Taoism are also detected in the Summer palace.

The King Dragon Temple on the South Lake Isle in the south and the Phoenix Terrace are a reference to the balance of yin and yang, a Taoist legacy. But the terrace we see today is only the ruins of the structure that was pulled down by Emperor Daoguang in an attempt to balance the masculine and feminine elements of the imperial households.

And the bronze ox on the east shore of the lake is in pair with the Tilling and Weaving Portrait on the west shore, referring to the association of Altair and Vega, two stars that are considered in Chinese astrology as a farm worker and his weaving wife. A family-based petty agriculture is the ideal economy of ancient China. Similar examples are seen everywhere in the Summer Palace.

These houses look out of place in this splendid garden. But this is the way the owner of the palace wanted it. The courtyard is called blissful farmhouse. The tile roof, the plain windows and doors make it like a farm cottage indeed. There used to be a fence-girded vegetable garden in front. Eunuchs and maidens came and planted grains and vegetables every spring for Empress Dowager Ci Xi, who came and did the ceremonial harvest in autumn to show her concern with agriculture and the livelihood of the peasants.

The commercial street at the rear of the Summer Palace is also a symbol of an easy contact of the rulers with the people. The street, otherwise known as Suzhou Street, is a miniature of the commercial streets of south China. Stationery shops, art crafts shops, shoe shops, cloth shops and restaurants line the banks of the river. Eunuchs and maidens would dress themselves as dealers and shoppers when the royal family came. Sounds of hawking and bargaining passed the street for a busy shopping district. But no business was done here. They were there just for show.

Empress Dowager Ci Xi was the real lord of the palace. The whole garden belonged to her. The virtual ruler of Chinese Empire spent most of her time in the Summer Palace. She slept in the hall of Happiness and Longevity, was saluted by her ministers in the Hall of Clouds, worked in the Hall of Benevolence and Longevity and had walks after lunch at the Painted Gallery. After a short nap, she would go and watch plays in Dehe Palace.

The playhouse in Dehe Palace is one of the three survival ancient playhouses in China. The three-story playhouse is 21 metres in height, higher than Changyin Playhouse in the Forbidden City and Qingyin Playhouse in Chengde Summer Retreat. The ground stage is 17 metres broad. Channels in the ceilings and floors make the stages mutually accessible.

The machinery in the attic facilitates mystical plays that may require extraordinary properties and stage effect. The stage effect can be very baroque, with snow flakes falling from the ceilings and water sprouting from under the floor.

Huge vats are buried under the ground stage, which not only provide water for the desired effect on stage but contribute to the sound resonation as the actors talk and sing. The empress was a Peking Opera lover and she demanded that her ministers share her hobby. It was supposed to be a special honor to be allowed to watch plays with her majesty and only a few got it. However those who were considered fortunate enough to get the honor didn’t always seem to enjoy it.

It was a long, tedious duty, which had to be served in patience and self control. Smoking was forbidden when her majesty was watching plays. The ministers addicted to opium had to make do without the drug and wait till the play was over.

As a result the ministers who were so honored to be treated with a show would either pretend to be ill and ask for leave or send their subordinates instead. But the empress was a great Peking Opera critic and she contributed profoundly to the development and prevalence of this performing art.

Famous artists such as Tan Xinpei, Yang Xiaolou, Wang Yaoqing, Jin Xiushan and Gongyunfu all served in the Summer palace. Many provincial theatrical companies were summoned too.

In the 13 years from the 21st year of Emperor Guangxu when the playhouse was completed till the empress dowager died in the 34th year of Emperor Guangxu she watched over 300 performances in the Dehe Palace and she didn’t stop watching Peking Opera until the month before her death.

The empress dowager was in the habit of checking the performance with the play script which she never watched a play without holding in hand. She paid attention to the costume, singing and dialogue, music accompaniment, martial art and facial expression and the accuracy of pronunciation. A slight error would lead this unsparing critic to stop the performance for instruction until the error was corrected.

And the actors all did their best, seeing to it that they presented the perfect show to patroness. These forerunners gradually developed Peking Opera into an advanced and popular performing art.

The standardization of the performance and the play script, the improvement by generations of Peking Opera masters and the refinement by literate audience in the imperial court contributed to the maturity of Beijing Opera.

And, very unexpectedly, the playhouse in the summer Palace became the cradle of Beijing Opera.

Amarble boat sits on the edge of kunming Lake on the west of Longevity hill opposite the playhouse. It is called qingyan Boat.

The British and French troops destroyed the cabins of the boat on October 18, 1860. When the boat was repaired the empress had the boat converted by western style, flanking the bulk with marble peddles and erecting western cabins with painted class and exotic patterns. The draining system is very well designed which channels rain water from the roof into the pipes.

And discharges the water through the gargoyles into the lake.

When she didn’t watch Peking Opera the empress would come to the marble boat for a change where she enjoyed the peace and quiet on the lake. She gave the name Qingyan to this boat.

|