In 1943, the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression in China had been going on for six years. It entered the most difficult stage of strategic stalemate. In 1943, the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression in China had been going on for six years. It entered the most difficult stage of strategic stalemate.

On a cloudy winter day, a group of foreigners came to the Eighth Route Army’s Liaison Office in Chongqing.

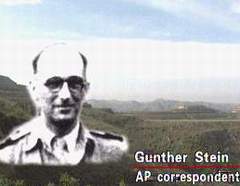

Visitors came here every day, rain or shine. Among this group of visitors were Atkinson of the New York Times, H. Foreman of UPI and The Times, Gunther Stein of AP and Israel Epstein of the Time weekly. They interviewed Dong Biwu and expressed their wish to visit the areas led by the Communist Party.

Dong Biwu said there were no fundamental disputes between the Chinese Communist Party and the Kuomintang, because the former also favoured the basic ideas of Sun Yat-sen’s Three People’s Principles. Since the outbreak of the war in 1937, he went on, the Communist Party had done nothing against the Three People’s Principles. Dong Biwu said the foreign journalists could see with their own eyes if they made on-the-spot investigations.

At a guesthouse on the south bank of the Jialing River, the journalists wrote their reports on this interview. But their reports were pigeonholed by the Kuomintang press censors.

The angered foreign journalists decided to act in unison. They wrote a joint letter to Chiang Kai-shek, demanding a tour of Yan’an.

They waited impatiently for many days. At last six foreign journalists had their wish fulfilled and travelled to Yan’an. This would make a breach in the news blackout imposed by the Kuomintang since the Southern Anhui Incident in 1941.

Yan’an extended a hearty welcome to the guests from afar.

As compared with foggy and cloudy Chongqing, Yan’an presented another picture for the foreign journalists. The vast highland, the dry climate and the bright sunshine made them very happy.

As compared with foggy and cloudy Chongqing, Yan’an presented another picture for the foreign journalists. The vast highland, the dry climate and the bright sunshine made them very happy.

Gunther Stein described Yan’an as a calm and clean village, like a college campus of the Middle Ages rather than the military and political centre of the Chinese Communist Party, where the sun was playing a peaceful and lively rustic melody on the semi-waste but exceptionally attractive land.

This was Yangjialing, the general headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party. Many strategic decisions had been made here since the beginning of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.

Here the Seventh National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party was held from April 23 to June 11, 1945. It formulated the epoch-making strategic line.

The foreign journalists found it very free to deal with the Communists. They did not see any over-elaborate formalities in official circles.

Earlier, Edgar Snow, the first foreign journalist visiting Northern Shaanxi Province, had been renowned worldwide. In those days, Bao’an was the red capital. Shortly after he left Bao’an, the red capital was moved to Yan’an.

Earlier, Edgar Snow, the first foreign journalist visiting Northern Shaanxi Province, had been renowned worldwide. In those days, Bao’an was the red capital. Shortly after he left Bao’an, the red capital was moved to Yan’an.

At the beginning of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, many foreign journalists were attracted to Yan’an by its reputation. They included Agnes Smedley, Edgar Snow’s wife Helen, James Bertram, Steel and Bosshard, a press photographer of a newspaper in Zurich. Owen Lattimore had been a journalist, but he came as a scholar.

Israel Epstein and five other foreign journalists jointly interviewed Mao Zedong. In a strong Xiangtan accent, he told them about the War of Resistance. Happily he had photos taken together with the foreign journalists.

The Communists would not let any opportunity slip by to propagate their anti-Japanese position to the world. Edgar Snow seized this opportunity. He was allowed to have long conversations with Mao Zedong and many other high-level members of the Chinese Communist Party. It was for the first time that Mao Zedong opened up his heart to this foreign journalist. Edgar Snow felt as if he had obtained a rare treasure.

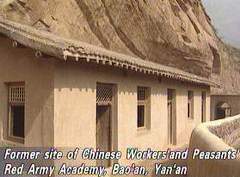

The Chinese Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army Academy was the predecessor of the Anti-Japanese Military and Political College. Students of the Red Army Academy used stone caves as classrooms, stone walls as blackboards and stones as desks and chairs. They attended classes under trees and in the open air. They established their academy with their own hands.

The lamp in Mao Zedong’s cave often gave light all through the night. He told Edgar Snow about his life experiences. This was the only self-introduction for Mao Zedong.

Liu Lizhen still remembers her impressions she gained when she saw foreigners for the first time.

In those days, everybody had to go to Yan’an by way of Xi’an. It was the starting point of the Silk Road built more than 2,000 years before. In the 1930s and 1940s, many foreign journalists and friends started from here to go to Yan’an.

It was a road of hardships and dangers, but the blockade lines could not block the curiosity of foreign journalists. James Bertram, a correspondent of The Times, hid under rice bags in a lorry of the Eighth Route Army when he travelled to Yan’an.

In Yan’an, James Bertram was accorded a warm welcome. He was invited to attend a graduation ceremony of the Anti-Japanese Military and Political College.

For the first time he saw Mao Zedong who was delivering a speech. He was impressed by the wisdom and charm of the peasant leader. He found Yan’an was a place permeated with an atmosphere of democracy and equality absent in the Kuomintang-controlled areas, a place with vigour and a force of tenacious resistance to Japanese aggression.

Later James Bertram recalled that he had a series of interviews with Mao Zedong in the following weeks and all those interviews were held in the evening, because that was the best time for him to work. Mao leaned against a deck chair and read telegrams coming continuously from the front. He wrote something on each telegram, handed it to an assistant and continued to talk about Bertram’s long list of questions.

Later James Bertram recalled that he had a series of interviews with Mao Zedong in the following weeks and all those interviews were held in the evening, because that was the best time for him to work. Mao leaned against a deck chair and read telegrams coming continuously from the front. He wrote something on each telegram, handed it to an assistant and continued to talk about Bertram’s long list of questions.

Bertram observed Mao Zedong almost with a feeling of admiration. Sometimes, Mao Zedong gazed at the night scene outside the window. Sometimes he touched his prominent forehead. Sometimes he tapped the nevus of good luck on his lower jaw. Bertram felt Mao Zedong was the incarnation of Zhuge Liang who could foresee with divine precision.

Mao Zedong’s talk with Bertram was published on October 25, 1937 under the title “Interview with the British Journalist James Bertram”.

Owen Lattimore and other foreign journalists came to Yan’an a few months earlier than James Bertram. They had much more trouble during their travel.

In early June, 1937, they pretended to be tourists, got to Taiyuan from Beijing, went southward to Xi’an by train and finally arrived in Yan’an.

Owen Lattimore found that Mao Zedong was willing to talk for hours with the Americans he had never met before. Their questions were very simple, but Mao talked patiently with the simplest terms.

The yangge dance was the pick of folk culture in northern Shaanxi Province. This rustic form of art was almost the only way of recreation in Yan’an. Agnes Smedley changed the situation. She introduced the social dance to Yan’an. It was her great innovation.

Smedley gave a course of dancing in a Catholic church. She selected some old records and used a hand gramophone. Mao Zedong, Zhu De, Zhou Enlai, He Long and other leaders attended the course in the evening. They were taught to dance by Smedley and her interpreter Wu Lili, an actress from Shanghai. But Peng Dehuai would rather sit by. The foreign journalists danced to the music from the old records. They were curious about the atmosphere in Yan’an different from that in Chongqing.

Smedley gave a course of dancing in a Catholic church. She selected some old records and used a hand gramophone. Mao Zedong, Zhu De, Zhou Enlai, He Long and other leaders attended the course in the evening. They were taught to dance by Smedley and her interpreter Wu Lili, an actress from Shanghai. But Peng Dehuai would rather sit by. The foreign journalists danced to the music from the old records. They were curious about the atmosphere in Yan’an different from that in Chongqing.

Tens of years have passed. Qiao’ergou Church is now the site of the Yan’an Lu Xun Art School. The yangge dance is still a required course for the students.

After his tour of Yan’an, Gunther Stein wrote a book entitled The Challenge of Red China. He said Yan’an was permeated with a lively and natural atmosphere and it seemed that the American officers and men were fascinated by the happy, enthusiastic and practical Eighth Route Army soldiers.

James Bertram had been well known for his coverage of the Xi’an Incident. He discovered something interesting. The foreign journalists each showed favour to a leader of the Chinese Communist Party. Edgar Snow showed favour to Mao Zedong, Agnes Smedley to Zhu De, Helen Snow to the women revolutionaries in Yan’an and he himself to He Long.

Edgar Snow was the first man who successfully displayed Mao Zedong’s image to the world. To make it easier for American readers to understand, he even compared him to Abraham Lincoln, a great man known to every American family. Snow said, Mao Zedong was a very interesting and complicated figure with the simple and true character of Chinese peasants. He said, Mao had a sense of humour and loved to smile innocently. Even when he spoke of himself and the shortcomings of the Soviet political power, he smiled all over. But the childish smile did not shake his conviction. He spoke amiably and led a simple life. Some people thought he was a bit vulgar, but he combined a strange quality of unaffectedness and simplicity with acute resourcefulness and shrewdness.

When Agnes Smedley saw Zhu De for the first time, it was an ordinary but lively scene. She described it in her book The Great Road. She saw a short but robust serviceman in his blue uniform getting up at a desk with a candle on it. She saw Zhu De she had mentioned again and again in her writing over the years. Indeed, he looked like the father of the Red Army. Gentle and friendly, he was over fifty, with deep wrinkles on his face. His thick lips cracked a smile of welcome. He extended out his hand to her and she kissed his cheeks.

Zhu De looked like a kindly father. He was also a general, brave and skilful in battle.

Gunter Stein came to Yan’an in 1944. He was deeply impressed by Nie Rongzhen. In his book The Challenge of Red China, Stein described General Nie Rongzhen as a tall and thin man who looked younger than his age of 46. Nie was dressed in a cotton-cloth uniform like an ordinary soldier, but more neatly than anybody else Stein had seen in Yan’an. His long face, like his whole, looked resourceful, displaying extraordinary stamina, discipline and boldness of vision. But he was very kind, modest and humorous.

A few months later in Chongqing, Baker saw Gunther Stein and others who had come back from Yan’an. Baker would submit to the U.S. State Department an analytical report on the foreign journalists’ tour of Yan’an.

When he talked with the journalists, Baker found that their tour had made a great impact on them. Both Baker and the journalists felt that the discrepancy between the Communist Party and the Kuomintang was so great and conspicuous that it was impossible to prevent the outbreak of a civil war. They believed that the Communists would most hopefully win the civil war.

After the victory of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, Chiang Kai-shek prepared to launch a civil war with the support of the U.S. government. The peaceful life in Yan’an began to change.

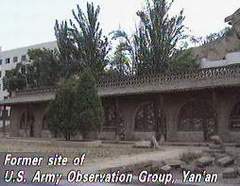

In August 1946, 60-year-old Anna Louise Strong flew to Yan’an from Beiping by a plane of the U.S. Military Mediation Office. She stayed at a cave dwelling of the U.S. Army’s observation group known as the “American Compound”.

In August 1946, 60-year-old Anna Louise Strong flew to Yan’an from Beiping by a plane of the U.S. Military Mediation Office. She stayed at a cave dwelling of the U.S. Army’s observation group known as the “American Compound”.

When he talked with Anna Louise Strong who had come to China again, Mao Zedong was full of confidence in the coming victory.

Anna Louise Strong had come to China on several occasions since 1925. She interviewed prominent figures like Feng Yuxiang, Wu Peifu, Soong Ching Ling and Mikhail Markovich Borodin. But her interview with Mao Zedong became a work that would be handed down to posterity. At the stone table and stools under this pear-leaved crabapple tree, Mao Zedong told her metaphorically that “all reactionaries are paper tigers”. This famous statement was known to the whole world.

Over two years later in January 1947, General George Marshall who had come to mediate between the conflicting Kuomintang and Communist Party left China sadly after he failed to fulfill his political mission.

Theodore White, a correspondent of the Time weekly in Chongqing, wrote a letter to George Marshall. He said the power to make decisions on the question of China was in the hands of millions upon millions of peasants, and the peasants living in small villages were the foundation of revolution and politics. It seemed that this journalist had a better understanding of the Chinese revolution than the senior soldier and politician.

The trial of strength between the Kuomintang and the Communist Party moved from the conference table to the battleground. In February 1947, eleven American journalists joined the last group of the Chinese Communist Party personnel of the Executive Headquarters for Military Mediation withdrawing from Nanjing to Yan’an. They made their last joint interview in the sacred place of the Chinese revolution. After the interview, John Roderick, an AP reporter, described how he left Yan’an. He found that Mao Zedong with a woolen scarf round his neck was standing on the runway of the Yan’an airport and lost in thought while gazing at the mountain valley in the distance. Roderick walked up to Mao. The chairman of the Chinese Communist Party extended his hand smilingly and asked him to write exactly what he had seen in Yan’an. Roderick said the prospects of communism in China seemed to be gloomy and asked what would occur in the future. Smiling indifferently, Mao Zedong called Roderick by his Chinese name and said, “I invite you to see me in Beiping in two years.”

Exactly two years later in 1949, one day in February, Steel, a reporter of the New York Herald Tribune, witnessed the Liberation Army entering the city of Beiping. He saw hundreds of American military trucks captured from the Kuomintang troops and dozens of American cannons.

In the days when the Liberation Army forces were encircling Beiping, the American weekly Life showed its peculiar sensitivity. It invited Henri Cartier Bresson, a well-known French press photographer, to take photos all over Beijing. On January 3, 1949, the Life weekly published photos taken by Bresson in Beiping. Entitled “A Last Look at Beiping”, the group of photos had captions on Taijiquan, people at secondhand bookstalls, teahouses, the Forbidden City, lanes, troops and policemen, bird fanciers and funerals. Bresson observed the city of Beijing in the great historical turmoil and recorded the residents and culture of Beijing with his unique way of photography. It seemed to the Americans that the gain or loss of Beijing would determine the destiny of China.

After the peaceful liberation of Beiping, editors of the Life weekly showed unusual ingenuity when they published another group of photos under the title “The Rise and Fall of the Kuomintang”. It reviewed the annals of China in half a century and finally focussed on the three great men of the Chinese Communist Party.

|