On Nov. 14, 1936, China Weekly Review printed a write-up by Edgar Snow entitled “Interviews with Mao Zedong, Communist Leader”. A month later, Mao Zedong appeared in the US “Life” magazine under the title of “First Pictures of China’s Roving Communists”.

Beside Snow’s consummate photograph of Mao Zedong was a note: Mao is his name. His head is worth $250,000. Many mysterious Communists who had remained unknown to the outside world for about 10 years made their first appearance to Western readers. Agnes Smedley wrote an editor’s note to the picture, stating that the army of the Chinese Communist Party was almost mysterious. For nearly 10 years, their whereabouts was uncertain. Their leader Mao Zedong was regarded as the “Chinese Stalin” or the “Chinese Lincoln”.

After Time made a success, the US news giant Henry Robinson Luce published another magazine Life, a journal distinguished by its pictorial effect. Born in China in a missionary family, Luce found it hard to cut his destined ties with China. He made China an indispensable and important part of the content of “Life” since its publication in 1923. Eminent Chinese political personages like Sun Yat-sen, Soong Ching Ling, Zhang Zuolin, Zhang Zongchang, Puyi, Chiang Kaishek, Soong Mei Ling and T. V. Soong appeared one by one in the journal.

Chiang Kaishek appeared on the cover of Time as early as April 4, 1927. Luce regarded him as a leader of an era. Yet, in early 1937, the same Luce realized through the Xian Incident the possibility of a united front of resistance against Japan when his sensitivity as a news reporter got the better of his political inclination.

Chiang Kaishek appeared on the cover of Time as early as April 4, 1927. Luce regarded him as a leader of an era. Yet, in early 1937, the same Luce realized through the Xian Incident the possibility of a united front of resistance against Japan when his sensitivity as a news reporter got the better of his political inclination.

In the spring of 1937, Luce and many foreign reporters seemed to hear the booming cannons of the approaching war.

Six months later, on July 7, 1937, Lugouqiao Bridge became the focus of world attention. China started a full-scale resistance war against Japanese invaders. All foreign journalists in China were to witness a vigorous and brutal war on the land of China.

After the July 7 Incident, the Nationalist Government exercised restrain and carried out a policy of non-resistance. As a result, Beijing and Tianjin fell into Japanese hands. The war spread to Shanghai in early August. Nanjing was occupied in December. In a mere six months, the Japanese troops controlled many important cities in the interior of China.

As the war spread rapidly, foreign journalists in China began to report on the war, exposing to the world the sufferings in China as eyewitnesses. Time and again, they recounted Japanese atrocities in China. Many of the reports were extremely touching and had a great international impact. The attention of the world was drawn to “suffering China”.

On March 19, 1938, China Weekly Review in Shanghai published a supplement called “Destruction of China”. It carried an article by a US journalist entitled “Suzhou in Terror” describing the deaths and destruction he saw when he entered the city at dawn. Words failed to describe the tragic scene, he said. He was heavily weighed down by sadness. The only consoling sight was a Chinese priest taking a thousand refugees to Guangfu.

Helen Foster Snow was spending a few months in Yan,an when the war broke out. She was the only Western journalist in Yan’an at the end of 1937. Her impression of Yan’an was that life was orderly although the atmosphere was tense. The Red Army was in readiness to set out to the front in 5 minutes. The July 7 Incident added to their eagerness to set out.

Agnes Smedley wrote in her diary on Oct. 23, 1937 that she was writing in the headquarters of the Eighth Route Army where she had been for the past months. She even took part in military activities and gave a great deal of publicity to the struggle against Japanese invaders. She often followed Zhu De around. This visit made her an authority on Zhu De’s life.

The city of Wuhan in central China was strategically important. After the Japanese troops occupied Nanjing near the end of 1937, the Nationalist Government retreated to Hankou. Wuhan became a wartime capital.

Wuhan became an important city where people were united in the fight against Japanese invaders. Many Western institutions in China moved to Wuhan. So was the Office of the Eighth Route Army in Nanjing. Zhou Enlai was appointed vice director of the political department of Nationalist Government’s military commission.

The American military officers who were to influence the situation in China in a few years gathered there too. This was a picture of a military attach岢 of the US Embassy.

Foreign friends who supported China in its fight against the aggressors gathered there and experienced the Chinese people’s enthusiasm in their resistance struggle. Edgar Snow appeared again in the dangerous parts of China. Almost every day he dispatched news to the United States to a much-read column of the weekly “Life”. Agnes Smedley was among the journalists too. In the eyes of foreign journalists, the Chinese people’s enthusiasm of the resistance war was rising to an unprecedented height.

Foreign friends who supported China in its fight against the aggressors gathered there and experienced the Chinese people’s enthusiasm in their resistance struggle. Edgar Snow appeared again in the dangerous parts of China. Almost every day he dispatched news to the United States to a much-read column of the weekly “Life”. Agnes Smedley was among the journalists too. In the eyes of foreign journalists, the Chinese people’s enthusiasm of the resistance war was rising to an unprecedented height.

Later, Bertram narrated what he saw in his memoir that Hankou was bombed in waves every day. Now and then, Madame Chiang’s remaining planes and planes manned by American, Italian and Russian pilots flew up to defend the city. It was becoming more and more like Madrid, a frontal capital that won public support. Unlike poor Nanjing that was forsaken and trampled on, it stood erect proudly as it persisted in the resistance war.

Israel Epstein came to China as a correspondent of the United Press of America. This picture was taken after the victory of the battle at Taierzhuang.

From June to October 1938, when both the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party accepted the slogan “Defend Wuhan”, the Chinese troops waged the famous Battle in Wuhan.

Agnes Smedley said in the feeling that the Battle in Wuhan was a great motivation to the Chinese people. She met a couple of US military observers who had been to the front. They told her that the north China troops, which were considered feudal and backward before, fought ever so valiantly.

The 5-month long Battle at Wuhan wore down Japan’s effective troop strength and brought about a turning point for the Anti-Japanese War, which turned from a strategic defense into strategic stalemate. That was also a period when the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party cooperated the best. Many journalists were able to talk to representatives from the Chinese Communist Party. They were deeply impressed by Zhou Enlai and Ye Jianying. Dutch director Joris Ivens had taken this valuable film outside the Eighth Route Army’s Office in Hankou.

Japanese troops occupied Hankou in October 1938 and Wuhan fell into enemy hands. The Nationalist Government had moved to Chongqing before the occupation. Then, factories, schools and refugees began to move to Chongqing too and started an unprecedented large-scale migration in modern Chinese history. Among the crowds of refugees were many foreign journalists. The journey was an unforgettable tragic experience to many people.

They climbed the Wushan Mountain, went through Fuling, Tangjiatuo and arrived at Chaotianmen, Chongqing. Facing the Yangtze River, Chaotianmen was the pivot of water transportation of Chongqing. Starting from Nov. 1937, over 600,000 refugees and tens of thousands of tons of material passed through Chaotianmen to Chongqing. Originally a distributing center of agricultural produce, Chongqing suddenly became the political, military, economical and cultural center of China. It became a wartime capital for as long as 7 years.

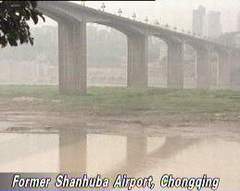

This small island in Chongqing called Shanhuba was known around the world during the war. It was an airport during the low-water season. Planes had to take off from Hong Kong in the night only when weather was extremely bad. During flood season, planes had to land at the Baishiyi air force base. In those years, countless important foreign and Chinese personages who had great influence on the political situation and foreign journalists had alighted and boarded the planes at Shanhuba. They alighted from the plane, went up the hill and down the slope, or boarded a plane and vanished in the night sky.

This small island in Chongqing called Shanhuba was known around the world during the war. It was an airport during the low-water season. Planes had to take off from Hong Kong in the night only when weather was extremely bad. During flood season, planes had to land at the Baishiyi air force base. In those years, countless important foreign and Chinese personages who had great influence on the political situation and foreign journalists had alighted and boarded the planes at Shanhuba. They alighted from the plane, went up the hill and down the slope, or boarded a plane and vanished in the night sky.

Walking on pebbles on the riverbank and up winding slated paths, new arrivals would find Chongqing both a curious and an intimidating place. Few of them had imagined they would spend 8 years in this damp mountain city. To be carried in a bamboo chair was a frightening experience to them.

A simple crude two-storied building on the southern bank of the Jialing River became the Press Hostel. One journalist said that when they arrived, government officials and diplomats had already taken up the better houses in the city. They were assigned to live in a shoddy structure. This Press Hostel was originally a school.

Graham Peck came to this hostel in 1940. He was a very special journalist as he was also an official of the United States Information Agency and a painter. He sketched the location of the hostel. Peck’s vivid portraits were valuable historical records of Chongqing. Many journalists claimed that all through their career as journalists they had been the busiest in Chongqing.

When winter made way for spring the skies of foggy Chongqing finally cleared up. Chongqing without fog was a difficult period for the city. With the bright sun came dense fleets of Japanese bombers. Peck had made quite a few sketches about the bombing of Chongqing. From Feb. 18, 1938 to Aug. 23, 1943, following orders from Emperor Hirohito and the supreme headquarters, the Japanese air force bombarded Chongqing for 5 years and a half. They called it “political bombing” or “strategic bombing”. One US journalist said that the bombing that was a horror to the atmospheric layer had slipped away from people’s memory. Yet the Japanese had invented a continuously escalating violence.

When winter made way for spring the skies of foggy Chongqing finally cleared up. Chongqing without fog was a difficult period for the city. With the bright sun came dense fleets of Japanese bombers. Peck had made quite a few sketches about the bombing of Chongqing. From Feb. 18, 1938 to Aug. 23, 1943, following orders from Emperor Hirohito and the supreme headquarters, the Japanese air force bombarded Chongqing for 5 years and a half. They called it “political bombing” or “strategic bombing”. One US journalist said that the bombing that was a horror to the atmospheric layer had slipped away from people’s memory. Yet the Japanese had invented a continuously escalating violence.

This journalist was called Theodore White. He came to Chongqing at 23 as an official of the United States Information Agency on the recommendation of his professor John King Fairbank in Harvard. Thanks to his outstanding talents, he soon became Time’s Far East chief correspondent. The bombing left a deep impression on him. He recorded that on May 3, 1939 when he and his journalist friends had barely come to the riverside, anti-aircraft alarms went off from all directions. Following a roaring sound of approaching planes a fleet of 27 Japanese bombers dotted the cloudless sky. On the hilltop overlooking the old city, his field of vision was widened. He saw fires raging in big and small valleys of the new city.

During the bombardment, the three Soong sisters who had been split apart by differing political views appeared together in public for the first time. The journalists recorded this rare scene.

The foreign girl standing with a notebook in her hand between Soong Mei Ling and Soong Ai Ling was US writer Emily Hahn. She was a columnist of “New Yorker”. She wrote a book about the three Soong sisters a few years later.

The foreign girl standing with a notebook in her hand between Soong Mei Ling and Soong Ai Ling was US writer Emily Hahn. She was a columnist of “New Yorker”. She wrote a book about the three Soong sisters a few years later.

Chongqing was “Free China” in the eyes of many journalists. Its people’s militant spirit frequently touched them. One US journalist claimed that all good-will journalists to China would admire Madame Chiang’s beauty, the generalissimo’s decisiveness, the Chinese army’s military prowess and the people’s noble spirit.

These impressions changed ever so quickly. Compared with Hankou during KMT-CPC cooperation, freedom dwindled in Chongqing. Kuomintang’s press censorship became an insurmountable barrier.

Watchful eyes often focused on the journalists. Compared with their lively life, their reports were gloomy and depressed and their write-ups about the war were increasingly pessimistic. Many journalists chose to leave than writing against the truth.

They played hide-and-seek on Chongqing’s narrow streets. The KMT propaganda department often revoked the license of foreign journalists, on the pretext of them having published “harmful statements on China”.

They played hide-and-seek on Chongqing’s narrow streets. The KMT propaganda department often revoked the license of foreign journalists, on the pretext of them having published “harmful statements on China”.

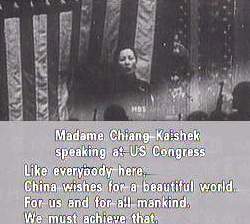

Illusions of foreign journalists began to shatter in 1943 when US media gave a large amount of publicity to Soong Mei Ling’s visit to the United States. Documentaries about China were shown in US cinemas.

Pearl Buck wrote an article in Life criticizing Soong Mei Ling. It exuded detest for Madame Chiang’s unpractical and exaggerated way of speech and for the way she had acted like a spoilt princess when she was a guest of President Roosevelt.

Pearl Buck’s article stunned the Americans. Daughter of a missionary priest, she had grown up in China and had deep feelings for China. She was known for her novel "Great Earth" and won a Nobel Prize in 1938. She had become an observer of China and had always appealed to the world to assist China.

At the same time, many journalists in Chongqing began to expose its decadence. Graham Peck satirized Chongqing with his cartoons. He depicted the grand feasting in the rear while situation in the front was tense. While the common people were supporting the front, wives of KMT officials were throwing their weight about. And while soldiers were fighting a bloody war, officials in the rear were wallowing in luxury and pleasure. Peck claimed that it was the people of Chongqing who had sustained this protracted war.

Barbara Stephens turned her attention to the Office of the Eighth Route Army. When this 21-year-old girl came to Chongqing to be a secretary of the United States Information Agency she had impressed many people with her charm. Inspired by her, photographer Jack Wilkers of “Life” published a set of photographs about Chongqing.

This American girl was excited by her contacts with the Communists. In a letter to her friend, she told him that she had many chances to meet with the Communists. She was particularly impressed with General Zhou Enlai. He was very charming. She died in an unexplained plane accident after the war. Her death was a riddle. Her experience in Chongqing was a beautiful memory of her brief life.

On Sept. 2, 1945, Japan surrendered and the signing ceremony was held on “The Missouri”. Theodore H. White was among the journalists who flocked over there. He rejected New York headquarters’ command to sing praises of Chiang Kaishek. In his return cable, he said it was wrong to continue to defend a dictator and his Kuomintang government.

On Sept. 2, 1945, Japan surrendered and the signing ceremony was held on “The Missouri”. Theodore H. White was among the journalists who flocked over there. He rejected New York headquarters’ command to sing praises of Chiang Kaishek. In his return cable, he said it was wrong to continue to defend a dictator and his Kuomintang government.

In 1946, “Thunder out of China” co-authored by Theodore H. White and Annalee Jacoby was published in America. White narrated his impression of Chiang Kaishek. He respected him at first, regretted for him next and despised him in the end. Chiang Kaishek had fallen from the pedestal of a hero in the heart of an American journalist.

|