Wuhan is a well-known city composed of the three towns of Wuchang, Hankou and Hanyang. After Zhang Zhidong initiated the Westernization Movement here one and a half centuries ago, Hankou began to prosper and it was reputed to be the Chicago of the Orient.

On October 9, 1911, dusk fell on Hankou and Wuchang across the Yangtze River. The river was rising as if a revolutionary storm was brewing.

In the small hours of the following day, revolutionaries fired at soldiers of the Qing Dynasty guarding the gate tower of Zhonghemen in Wuchang and captured the headquarters under the command of Li Yuanhong . Li crossed over with his troops.

In the small hours of the following day, revolutionaries fired at soldiers of the Qing Dynasty guarding the gate tower of Zhonghemen in Wuchang and captured the headquarters under the command of Li Yuanhong . Li crossed over with his troops.

The 18-starred flag fluttered over the residence of the military governor of Hubei Province. The new army’s gunshots sounded the death knell of the feudal monarchy which had reigned for thousands of years. In a few months, 18 provinces proclaimed independence one after another. The Revolution of 1911 spread to the whole country, turning Sun Yat-sen’s ideal into a reality.

In Beijing, the news of the Wuchang Uprising reached the Qing imperial court where the monarch and officials were discussing the formation of a constitutional government. Panic swept through the Forbidden City. Empress Dowager Longyu called the ministers to discuss the way to deal with the situation. They decided to move the Northern Army to press on towards Wuhan. A real trial of strength began. The revolutionary storm drew the attention of the world to the Orient once again. Two Australians were involved in this revolution. They formed indissoluble bonds with the annals of the Republic of China. One of them was George Morrison.

On October 11, the day after the uprising, Morrison sent the first special dispatch from Beijing to the newspaper The Times. The dispatch described the uprising as a great shock to the Qing government. It said that Beijing was scared by the outbreak of the revolution and the revolt of the army, and the Qing government was on the verge of destruction.

Morrison hurried to Hankou. The smoke of gunpowder had just been dispersed and Wuhan turned into a sea of jubilation. He stayed in Hankou for only five days. Between October 11 and 24, he sent dispatches of nearly ten thousand words to the newspaper The Times, covering the situation in Wuhan after the uprising. His impression was that not many people were killed, but the loss of their property was grave; the revolutionaries were highly disciplined, but the Northern Army committed raping and plundering. He said that the Qing government had to be overthrown and this might be the common aspiration of the people.

At that moment, Sun Yat-sen, the genuine leader of the revolution, was abroad and Huang Xing was in Hong Kong. Morrison did not see these famous figures, but from the ranks of revolutionaries he found his compatriot Henry Donald. He was a correspondent of the American newspaper The Herald.

On December 1, 1911, Henry Donald said in a dispatch sent to The Herald that a life-and-death struggle occurred between a city and a mountain in the morning, shells whistled over the top of Mount Zijin and the plains and shell fragments were scattered all around. He said there were almost no casualties on the part of the Chinese revolutionaries and the Qing soldiers were putting up a desperate struggle.

On December 1, 1911, Henry Donald said in a dispatch sent to The Herald that a life-and-death struggle occurred between a city and a mountain in the morning, shells whistled over the top of Mount Zijin and the plains and shell fragments were scattered all around. He said there were almost no casualties on the part of the Chinese revolutionaries and the Qing soldiers were putting up a desperate struggle.

The city he referred to in the dispatch was Nanjing and the mountain was Mount Zijin.

Flags of the Republic were flying in the provinces which had proclaimed independence in the Revolution of 1911, but Nanjing under the rule of Zhang Xun remained the last fortress of the Qing government. The war could be ended with the occupation of Nanjing. In November, the republican troops gathered in Zhenjiang, 40 miles down the Yangtze River, and got ready to attack Nanjing. Donald hurried there and ventured to go up Mount Zijin and inspect the movement of the Qing troops. He joined the soldiers in attacking Nanjing.

At dusk when the attack was still going on, Donald left the position and went to a railway telegraph office near the Gate of Peace. With a candle and a pencil, he drafted a dispatch to cover the battle.

Henry Donald was a born adventurer. He came to Hong Kong from Australia eight years before and began his career as a journalist in China. On the other side of Luohu Bridge, the Qing Dynasty was crumbling. As a correspondent of the Sydney newspaper Daily Telegraph, he went to Guangzhou to interview Zhang Renjun, Governor-General of Guangdong and Guangxi. He became Zhang’s honorary advisor.

Henry Donald was a born adventurer. He came to Hong Kong from Australia eight years before and began his career as a journalist in China. On the other side of Luohu Bridge, the Qing Dynasty was crumbling. As a correspondent of the Sydney newspaper Daily Telegraph, he went to Guangzhou to interview Zhang Renjun, Governor-General of Guangdong and Guangxi. He became Zhang’s honorary advisor.

In Guangzhou, Donald saw Morrison for the first time. Morrison introduced him to Soong Yao Ru, the father of the three sisters of the Soong family and a faithful supporter of Sun Yat-sen. During the conversation, the name of Sun Yat-sen was mentioned over and over again. Donald took an interest in Sun Yat-sen’s plan for revolution.

Donald felt that a revolution was inevitable. He decided to go to the centre of the storm. In the early spring of 1911, Shanghai appeared in front of him.In a park at the end of the road, he found Wu Tingfang, a revolutionary in Shanghai. After that he was closely connected with the revolutionary movement.

A few months later, the news of the success of the Wuchang Uprising reached Shanghai. On November 6, the revolutionaries captured the Jiangnan Arsenal and took Shanghai. Representatives from the independent provinces gathered in Shanghai to form the Provisional Government of the Republic of China. When they were debating who would be the head of the new republic, a man who enjoyed popular support returned from abroad. He was Sun Yat-sen, leader of the Chinese Revolutionary League.

On New Year’s Day 1912, Sun Yat-sen was sworn in as the Provisional President in Nanjing. After attending the inaugural ceremony, Henry Donald transmitted the important news to the whole world. On the day after he returned to Shanghai, he received a telegram from Sun Yat-sen. He was asked to draft a declaration of the government of the Republic. A few days later, people of the world saw what the Republic of China wanted to say, but they did not imagine that it had been typewritten by a young Australian journalist.

Revolutionaries took up important posts. A young man by the name of Chiang Kai-shek became the chief of staff in Hangzhou. He had heard Sun Yat-sen’s speeches in Japan. When he learned about the revolution, he hurried back from a military academy in Japan. He got to know Henry Donald before he arrived in Hangzhou. A few years later, Donald became his private advisor.

Revolutionaries took up important posts. A young man by the name of Chiang Kai-shek became the chief of staff in Hangzhou. He had heard Sun Yat-sen’s speeches in Japan. When he learned about the revolution, he hurried back from a military academy in Japan. He got to know Henry Donald before he arrived in Hangzhou. A few years later, Donald became his private advisor.

While flames of war were raging along the Yangtze River, Morrison followed developments in Beijing. He believed that more dramatic news would emerge here. A few days later, Yuan Shikai came to Beijing by train. He hurried directly to the Forbidden City. Empress Dowager Longyu and Emperor Xuantong pinned their last hopes on him.

When the Provisional Government in Nanjing was established, the war on the Wuhan front had not yet been over. Yuan Shikai sent more troops to put pressure on the south. At the same time, he sent representatives to hold secret talks with the government in the south. To overthrow the Qing Dynasty as quickly as possible and avoid the loss of more people’s lives and property, Sun Yat-sen declared that if Yuan Shikai could force the Qing court to abandon its power of its own accord and peace was negotiated between the south and the north, he would resign from the post of Provisional President and recommended Yuan for the post. Yuan employed both soft and hard tactics to compel the Qing court to abdicate. On February 12, Empress Dowager Longyu issued an imperial edict of abdication in the name of Emperor Xuantong.

Morrison immediately sent to The Times a dispatch about the abdication of the Qing emperor. It was known as the exclusive report of the year.

Two days later, Yuan Shikai became the Provisional President. He gave the position of political advisor to Morrison.

Two days later, Yuan Shikai became the Provisional President. He gave the position of political advisor to Morrison.

Yuan Shikai promulgated a series of decrees. One of them renamed Wangfujing Street, the most famous business street in Beijing, after Morrison. With the unexpected progress of the Chinese history, the fate of the two Australians turned for the worse.

Yuan Shikai was not satisfied after he became the President of the Republic. In 1914, he held a grand ceremony at the Imperial Ancestral Temple to offer sacrifices to Confucius. He made a reckless move to restore the monarchy.

Once again Beijing became the political centre of the country. Henry Donald hurried to Beijing from Shanghai to take over the Beijing office of the New York newspaper The Herald. He was concurrently the chief editor of the Far Eastern Review published in Shanghai. He returned to Shanghai once every month for the publication of this monthly magazine. He became an honoured guest of the new government and he was on the best terms with Finance Minister Zhou Ziqi among the senior officials.

One day in late January 1915 in Shanghai, Henry Donald was busy sending manuscripts of the Far Eastern Review to the printing shop. Suddenly he received an urgent telegram from Zhou Ziqi. It said: “Come back right away. It has something to do with the allied nations. The situation is serious.”

Excitedly Donald hurried to the railway station, anticipating a piece of important news.

Donald came out of the Beijing railway station and took a rickshaw to the U.S. legation. Lights coming through the shutters of shops along the streets went out. A busy day was over. Clatter of mah-jong was dimly heard. A baby cried.

Donald came out of the Beijing railway station and took a rickshaw to the U.S. legation. Lights coming through the shutters of shops along the streets went out. A busy day was over. Clatter of mah-jong was dimly heard. A baby cried.

When he arrived at the U.S. legation, Minister Paul Samuel Reinsch was waiting for him at the door. The minister was usually very calm, but now he was obviously worried. He told Donald that Yuan Shikai and the Japanese government were making a deal.

World War I broke out in 1914. Henry Donald persuaded the Chinese government to declare war on Germany in a hurry and recover the right of occupation in Shandong Province. On the night of January 18, 1915, the day when China recovered the right in Shandong, the Japanese minister Hioki came to the Temple of Heaven where he met with Yuan Shikai and read out Japan’s “strong dissatisfaction”. Striking a table heavily with his palm, he left behind a threatening document.

After the Japanese minister left, Yuan Shikai got very angry. Later a cabinet minister told Paul Reinsch tearfully that Japan had raised extremely harsh demands and if China accepted these demands, she would lose her independence and become Japan’s vassal state.

Henry Donald entered Finance Minister Zhou Ziqi’s mansion by night. Zhou did not dare to disclose the details. Donald said he would list all the demands Japan might make upon China and Zhou could delete those impossibilities with a pencil. They began a special conversation by writing.

Donald listed a number of demands and Zhou deleted some of them. With the elicitation method Zhou asked where arms and ammunition were made. Donald wrote the word “arsenal”. It was one of Japan’s demands to control the arsenal. So Donald wrote down the demands Japan might have made and Zhou confirmed them one by one. It turned out that Japan had demanded the control of several railways, development of mining industry and stationing of troops.

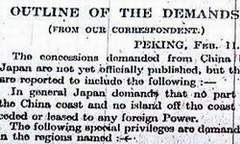

Donald immediately sent a dispatch to The Times, listing Japan’s demands and warning the world that a war in Asia might break out at any moment. He said, “The concessions demand from China by Japan are not yet officially published, but they are reported to include the following …”

But the dispatch did not arouse adequate attention.

On the night of the following day, Donald came to Morrison’s residence. After they talked for a while, Morrison stood up and said he would go to his study. Donald noticed that Morrison straightened out the papers on his desk and pressed some of the papers before he left his office.

Donald understood what Morrison meant. He walked up to the desk and put the papers into the pocket of his overcoat. It was the translation of the full text of Japan’s Twenty-one Demands on China.

Donald understood what Morrison meant. He walked up to the desk and put the papers into the pocket of his overcoat. It was the translation of the full text of Japan’s Twenty-one Demands on China.

Donald sent to The Times another dispatch covering all the 21 demands. It stirred up a public outcry. The strong reaction of the Chinese public had not been expected by Yuan Shikai. Li Dazhao, who was studying in Japan, issued the “Message to Fellow Countrymen”, calling on them to boycott the Twenty-one Demands.

On May 7, Japan sent another 30,000 troops to Shandong Province and warned the Chinese side to accept the Twenty-one Demands within 48 hours. At the same time, Chinese minister to Japan Lu Zongyu reported to Yuan Shikai that the Japanese government had hinted that it would support his plan to be the emperor if he accepted the Twenty-one Demands. On May 9, Yuan Shikai signed the revised Twenty-one Demands on the pretext that China was not strong enough to meet Japan on the battleground.

Yuan’s action shocked the world. On the same day, Peng Chao, a student in Hunan Province, threw himself into a river after he wrote a letter in his own blood.

Mao Zedong, who was then a young man, also wrote a message calling on the students to take revenge.

In Beijing, 200,000 people gathered at a rally in the Central Park. They donated one million yuan for a national salvation fund. In Shanghai, mass organizations sent a telegram to Yuan Shikai, expressing determined opposition to the Twenty-one Demands that meant national subjugation. In Tianjin, 17-year-old Zhou Enlai, a student of Nankai School, made a speech in the street, calling on the people to wipe out the national humiliation. The National Educational Association decided that May 9 would be the Day of National Humiliation every year.

Four years later, World War I ended with the victory of the Entente countries. These countries called the Paris Peace Conference to settle post-war problems. Morrison had returned to Britain. Although he was seriously ill, he attended the Paris Peace Conference as an advisor to the Chinese delegation. At the request of the Chinese students in France, the Chinese delegation demanded the abrogation of the Twenty-one Demands, but it was rejected at the conference.

On May 4, a dynamic protest movement broke out in Beijing. Morrison did not see the awakening of the Chinese people, but he immediately wrote a letter to ask about the situation in Beijing. A reporter of the Chicago Daily News in Beijing told him that excited students shouted in the streets, telling the passersby that the errors made by certain pro-Japanese members of the cabinet had brought great humiliation to the country. He said the students justifiably called these bureaucrats traitors bought over by the Japanese.

June 28 was the deadline for the signing of the peace treaty at the Paris Peace Conference. Gu Weijun, a young Chinese diplomat, and others refused to attend the signing ceremony. Morrison was in Britain. He said in a commentary that the text of the peace treaty was much worse for China than what she had expected and it was simply disastrous. He said he did not believe any living Chinese of good standing had the audacity to sign this treaty.

Morrison was seriously ill, but he thought of China all the time. A few days before he died, he said he hoped to go back to China. He said he did not want to die, but if he had to die, he would like to die in Beijing, to die among the Chinese who had loved him over the years. Plagued by both internal and external troubles, the Northern Government did not care for him. Morrison left the human world with his unfulfilled wishes.

Morrison was seriously ill, but he thought of China all the time. A few days before he died, he said he hoped to go back to China. He said he did not want to die, but if he had to die, he would like to die in Beijing, to die among the Chinese who had loved him over the years. Plagued by both internal and external troubles, the Northern Government did not care for him. Morrison left the human world with his unfulfilled wishes.

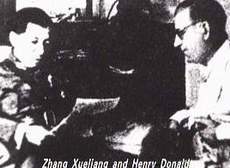

After the death of Sun Yat-sen, Henry Donald went to northeast China and became a private advisor to Zhang Xueliang. Donald believed that Zhang could rescue China most hopefully, but he was a drug addict. Donald urged him to stop taking drugs. After the September 18th Incident, Donald accompanied Zhang to recuperate in Europe. After he returned to China, Donald became a private advisor to Chiang Kai-shek and played a very important role in the Xi’an Incident. But Donald was disliked by Soong Mei-ling. He left China in anger. After the outbreak of the Pacific War, he stayed at a POW camp set up by Japanese troops in Manila for four years. He contracted a serious illness. After the war he was sent to an American navy hospital in Honolulu for treatment.

In November 1946, Henry Donald returned to Shanghai. At Hong’en Hospital his illness was diagnosed as terminal lung cancer. Donald knew his own position. He had returned to China to find his final settling place. After he died, he was buried at Shanghai International Cemetery. His gravestone cannot be found now. It is said that he was buried at the side of the grave of Soong Yao Ru. It was through Soong Yao Ru that Henry Donald got to know Sun Yat-sen’s cause and entered the annals of the Republic of China. This Australian devoted himself to China from the Revolution of 1911 to the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. His merits and demerits are to be judged by people of the future generations.

|