In 1894, one Australian became a special correspondent in China of the influential Times for his legendary 3,000-km travel from Shanghai to Rangoon with only 18 pounds in his pocket. He was called Morrison. In 1894, one Australian became a special correspondent in China of the influential Times for his legendary 3,000-km travel from Shanghai to Rangoon with only 18 pounds in his pocket. He was called Morrison.

When Morrison started out in a Chinese outfit with Chinese porters on a journey across China, it had never occurred to him that he would become a world-renowned correspondent a few years later in an event that stirred the world.

The Church had triggered the storm. Starting from Matteo Ricci, the Church had always wanted to make an expedition into China. Five emperors of the Qing Dynasty from Kangxi to Daoguang had boycotted the entrance of the Church into China. In the middle of the 19th century, under the cover of strong ships and powerful cannons, large numbers of missionaries streamed into China. Emperor Daoguang was forced to lift the ban in 1844. Very soon, large-scale missionary activities spread across China to the detriment of the people’s interests. Cathedrals sprang up like mushrooms in places like Hebei and Shandong provinces. By the end of the 19th century, more than 500 missionary stations spread out in Chinese villages. In the end a campaign against foreign religion broke out.

In Xibiaobei Hutong in east Beijing, one Ming-dynasty architectural complex is still in good shape. It was the residence of Yu Qian, vice war minister of the Ming Dynasty. He opposed moving the capital to the south and fought and defended Beijing when powerful enemy in the north tried to overthrow the Ming Dynasty. The Ming Dynasty was finally replaced by the Qing and time went on. This architectural complex had witnessed the vicissitudes of the last centuries. Its owners changed many times, but its brick carvings and stone steps have remained the same.

The complex suddenly became the focus of Beijing in April 1900 during the upsurge of Yihetuan Movement when Yihetuan set up their first association that consisted of a hundred and more members in it. The Movement that originated in Shandong soon spread to Hebei, Beijing and Tianjin in less than a year’s time.

On April 15, more than 100 Yihetuan members gathered at Lugouqiao outside Beijing, passing out notices against foreign powers and missionaries.

The turn of the century saw the most chaotic period in China, a period that altered the direction of the Chinese Empire. When the West was rejoicing over the arrival of the new century, the stamina that erupted in China would shake the world.

The turn of the century saw the most chaotic period in China, a period that altered the direction of the Chinese Empire. When the West was rejoicing over the arrival of the new century, the stamina that erupted in China would shake the world.

Dongjiaomin Lane was originally a very ordinary street of Beijing not far from the Forbidden City. It was originally called Dongjiangmi Lane. Running from east to west, it is crossed by several small south-north lanes. After the Opium War, it changed its name to Dongjiaomin Lane as foreign envoys stationed there. After the Second Opium War, foreign diplomatic corps began to build legations there.

In April 1900, the foreigners in Dongjiaomin Lane began to feel the Yihetuan impact. Their concern of the “Boxers”, who emerged in 1898 in Shandong, had begun at the end of 1899. On Jan. 27, 1900, ministers of Britain, America, France, Germany and Italy had presented a joint note to the Chinese Foreign Office requesting the Qing government to suppress Yihetuan.

Yihetuan’s notices of “Burn the cathedrals! Kill the Christians!” appeared in Beijing on April 29. Their spearhead was directed against foreigners in China. They tore up rails along the line from Lugouqiao to Baoding, burned down railway stations, demolished bridges and cut telegraph lines to the great horror of foreigners in Beijing.

On May 19, imperial diplomatic corps in the capital held a joint conference. They decided to call for military help from their governments. On June 4, they cabled their respective governments to send troops to Beijing.

Their cables streaming out from the French Post Office, their only channel to the outside world in Dongjiaomin Lane, stunned the European countries and America. In early June, “Times” published an “SOS” from its special correspondent Morrison. His concise cable had a greater impact than any political measures the foreign diplomats could think of. It became an important element for the British government to send expeditionary troops to China.

To recover and strengthen their colonial rule in China, Europe and America resorted to armed intervention. Britain moved troops from Hong Kong and Japan from Hiroshima. France sent warships from Vietnam and the Mediterranean and the USA from Manila. Tsarist Russia entered northeast China from Siberia. Germany appointed Alfred von Waldersee as allied commander-in-chief. The Eight-power Allied Forces, led by Waldersee, left Europe for China.

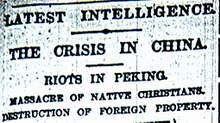

In the British Library in London, we looked up British newspapers from April to June l900. The front page of influential papers carried news about the situation in Beijing and the British legation in China. In the files, we came across the diary one British officer wrote in June 1900.

This officer recorded his expedition in China. He wrote that bad news from China made him receive orders to go to fight in China and thus turned a new page in his life.

This officer recorded his expedition in China. He wrote that bad news from China made him receive orders to go to fight in China and thus turned a new page in his life.

In Beijing, Morrison waited eagerly for the arrival of reinforcement. He sat before a map every day calculating their arrival date.

Unknown to Morrison was that 22 warships and cruisers of foreign powers were already assembled at Dagu forts, Tianjin. The allied forces launched a frenzied attack on Dagu on June 20 and took it in a few hours. 15,000 allied soldiers proceeded towards Tianjin on June 20. Their advance was slowed down by attacks of ambushed Yihetuan and the Qing army. On July 13, the allied forces stormed Tianjin by two routes. They lost some 800 men and took the city on the 14th.

On June 18, 1900, the British “Times” carried a dispatch by Morrison, the last piece of news from Beijing before foreign legations were besieged. The dispatch was written on June 14. “A serious anti-foreign outbreak took place last night when some of the best buildings in the eastern part of the city were burned and hundreds of native Christians and servants employed by foreigners were massacred within two miles of the Imperial Palace. It was an anxious night for all the foreigners who were collected under the protection of the foreign guards. The ‘Boxers’ burned the Roman Catholic East Cathedral, the largest of churches. If reinforcement of the foreign guards do not arrive today, the chaos might worsen. Reliable sources claimed that no Britons were hurt.” Morrison paid a man 20 taels of silver to send this dispatch out.

The legation area was besieged on the 20th. Morrison tried to send news to Tianjin by writing it on a piece of thin paper then soaking it in oil to make it waterproof. He put it in a bowl of gruel and entrusted it to a young Chinese Christian. But his attempt failed.

Since they got no news from Beijing, Western media turned to their special correspondent in Shanghai. On July 16, 1900, the British “Daily Mail” carried a dispatch of their special correspondent in Shanghai, which claimed that the foreign legations in Beijing were occupied and all Europeans killed. It claimed that all Europeans fought courageously to the end against sanguine savages. They fired their last bullets and faced death unflinchingly. This illusory account caused a strong reaction in Europe.

At this time the British troops had already arrived in Beijing. A war correspondent took this picture for them.

At this time the British troops had already arrived in Beijing. A war correspondent took this picture for them.

At dawn on Aug. 14, the Eight-power Allied Forces launched a general attack at Beijing. Vying for credit the Russian troops attacked Dongbianmen Gate, which was closer to the legations instead of Dongzhimen Gate according to plan. They fought a fierce battle against the tough resistance of the Qing troops and the Yihetuan.

Booming guns threw the Forbidden City into panic.

In the night of Aug. 14, the last column of the Eight-power Allied Forces entered the city of Beijing. In the small hours of the 15th, Empress Dowager Cixi disguised herself and fled, taking Emperor Guangxu with her. Before her departure, when Emperor Guangxu and Concubine Zhen paid their respects to the supreme ruler, Concubine Zhen pleaded for her to leave Emperor Guangxu behind to negotiate with the allied forces. Empress Dowager Cixi was so enraged that she ordered the eunuchs to throw Concubine Zhen down a well. She then fled from the Summer Palace to Juyong Pass, Badaling, Yanqing and straight to Xi'an.

At 5 a.m. British and American troops stormed Dongjiaomin Lane. The encirclement of the legation area and the Pehtang Cathedral was lifted. 40 years ago, it took the Anglo-French Allied Forces 40 days to proceed from Tianjin to Beijing. 40 years later, the same route took the Eight-power Allied Forces only 10 days. For an ancient country with thousands of years of history, for a nation, this was an unprecedented, greater humiliation than the failure of the Opium War. The capital of the Chinese Empire was turned to ruins by the Eight-power Allied Forces.

At 5 a.m. British and American troops stormed Dongjiaomin Lane. The encirclement of the legation area and the Pehtang Cathedral was lifted. 40 years ago, it took the Anglo-French Allied Forces 40 days to proceed from Tianjin to Beijing. 40 years later, the same route took the Eight-power Allied Forces only 10 days. For an ancient country with thousands of years of history, for a nation, this was an unprecedented, greater humiliation than the failure of the Opium War. The capital of the Chinese Empire was turned to ruins by the Eight-power Allied Forces.

The massacre began. Waldersee openly ordered his officers to punish China severely. Cries of fear erupted as the city was strewn with corpses. People recalled later: the foreigners killed countless people the day they entered the city.

Morrison, who had called for help, was stunned by the atrocities of the Allied Forces. When the besieged foreigners rejoiced over the arrival of the reinforcing troops, this Australian correspondent began to report on their plundering activities. On Aug. 17, he cabled Times that the Pehtang Cathedral was rescued. Foreign forces controlled Beijing. There was no government here. French and Russian flags flew in the best parts of the Forbidden City. The Empress Dowager Cixi, the Emperor and Prince Duan had fled to Taiyuan in Shanxi. Their destination might be Xi'an. “Beijing Public News” stopped publication on the 13th.

A Russian correspondent of “New Borderland” who was reporting about the Allied Forces described what he saw in Beijing that day: “Silence reigned at dusk. Rifle shots stopped. I climbed up the city wall again to look at the city. Frightening ammunition had been flying over the ancient city from 2 a.m. to 2 p.m. They were hot lead bullets, steel fragmentation shells and shells the Chinese had manufactured with wrought iron. The people shed blood for a whole 12 hours at the serene city walls of the sacred capital. The cloudless sky dimmed over at the deadening booms of bombardment.”

Two months after Beijing was occupied, a journalist who was sent by “Le Figaro” to cover Beijing came to a city of debris and ruins. “After fire and shell have crumbled away Beijing’s flimsy materials the city is only a mass of debris... It was all ruins. Flags of European countries flew over its walls.”

In the Forbidden City and the Temple of Heaven, places where serenity used to reign, the cavalry of the savages now galloped. Tens of thousands of Indian soldiers sent by Britain garrisoned there. Their horses trampled everything.

In the Forbidden City and the Temple of Heaven, places where serenity used to reign, the cavalry of the savages now galloped. Tens of thousands of Indian soldiers sent by Britain garrisoned there. Their horses trampled everything.

The pillaging of Beijing became a festival for the “victors”. While the Allied Forces were slaughtering the Chinese, their wives at home received many postcards from Beijing. Some reported their feats. Others sent a safety note in the Chinese traditional style. They constituted a unique form of the history of invasion. Behind their romantic behavior were the humiliation and the suffering of the Chinese people.

After their victorious entry into Beijing, the Allied Forces paraded through the Forbidden City. They entered Daqing Gate and held an “occupation ceremony” as they marched on the central slated path. At the Meridian Gate they made a show of their prowess. Then they marched into the palace, visited all the halls and jostled to take pictures at the throne. Then they started to plunder.

Alphonse Favier, bishop of Pehtang Cathedral, excelled in Beijing’s cultural relics. He guided the Allied Forces in their plunder and carnage. He also pointed out places for Christians to loot. The soldiers even scraped off the gilded gold on bronze vats in the palace.

The astronomical instruments of the ancient Beijing Observatory became important targets too. They were divided between French and German troops. Many were carried to the French legation in China. To manifest their victory over China, the German troops moved them back to Germany as trophies. After the First World War, after a period of 20 years, the Treaty of Versailles stipulated that they should be returned to China. Today, the ancient observatory is still relating without words the calamities it had suffered.

For about a year, Morrison exposed the brutality of Waldersee’s troops. On Sept. 24, Morrison cabled Times that the Russians were plundering the Summer Palace in an organized way. On Nov. 24, he reported that the Germans continued to harass places outside Beijing with an aim to loot. On Dec. 28, he reported that the Germans destroyed sacred architectures of imperial examinations. They burned the wood and built a German police station with the bricks. Cartoons like this appeared on British newspapers. The Chinese who killed foreigners were labeled barbaric while the foreigners who killed the Chinese were civilized.

Waldersee, allied commander-in-chief, was tremendously annoyed by Morrison’s continuous exposure of the atrocities of the Allied Force, particularly of the German forces. On Feb. 25, 1901, Waldersee wrote in his diary that Morrison exaggerated what he saw, like most British journalists were prone to do.

Waldersee, allied commander-in-chief, was tremendously annoyed by Morrison’s continuous exposure of the atrocities of the Allied Force, particularly of the German forces. On Feb. 25, 1901, Waldersee wrote in his diary that Morrison exaggerated what he saw, like most British journalists were prone to do.

On Oct. 11, 1900, Li Hongzhang who was to take part in truce talks arrived in Beijing under the escort of Russian troops. The toppling Qing Dynasty had placed its hope on this senile minister.

Foreign diplomats began to haggle. On Dec. 24, 1900, apart from the eight powers, Belgium, Spain and Holland joined in to divide the spoils. They jointly proposed a 12-article convention that was not to be altered.

New York Times gave a detailed description of the talks. Although the terms were harsh. Empress Dowager Cixi ordered Li Hongzhang to accept all since there was no intention to punish her. Foreign and Chinese plenipotentiaries negotiated for 9 months in Dongjiaomin Lane until the Qing government was forced to sign the humiliating Treaty of 1901 on Sept. 7, 1901. The signing of the Treaty of 1901 was a heavy blow to Li Hongzhang who died two months later. Yuan Shikai succeeded him and became Beiyang minister and viceroy of Zhili.

Morrison was once regarded as a source of trouble by foreign diplomats. Still in Beijing in 1912, he received in August a letter of appointment sent by Cai Tinggan, English secretary and interpreter of Yuan Shikai, president of Republic of China. He was appointed political advisor to the president for 5 years. Morrison started a new role in China.

|