The History of Rocket Science

2009-05-20 14:58 BJT

During the latter part of the 17th century, the scientific foundations for modern space travel was laid out by the great English scientist Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727). Newton organized his understanding of physical motion into three scientific laws. The laws explain how rockets work and why they are able to work in the vacuum of outer space. Newton's laws soon began to have a practical impact on the design of rockets. About 1720, a Dutch professor, Willem Gravesande, built model cars propelled by jets of steam. Experimenters and scientists in Germany and Russia began working with rockets with a mass of more than 45 kilograms. Some of these were so powerful that their escaping exhaust flames bored deep holes in the ground even before lift-off.

During the end of the 18th century and early into the 19th, rockets experienced a brief revival as a weapon of war. The success of Indian rocket barrages against the British in 1792 and again in 1799 caught the interest of an artillery expert, Colonel William Congreve. Congreve set out to design rockets for use by the British military.

The Congreve rockets were highly successful in battle. Used by British ships to pound Fort McHenry in the War of 1812, they inspired Francis Scott Key to write "the rockets' red glare," words in his poem that later became The Star- Spangled Banner.

Even with Congreve's work, scientists had not improved the accuracy of rockets much from the early days. The devastating nature of war rockets was not their accuracy or power, but their numbers. During a typical siege, thousands of them might be fired at the enemy. All over the world, researchers experimented with ways to improve accuracy. An English scientist, William Hale, developed a technique called spin stabilization. In this method, the escaping exhaust gases struck small vanes at the bottom of the rocket, causing it to spin much as a bullet does in flight. Variations of the principle are still used today.

Rockets continued to be used with success in battles all over the European continent. However, in a war with Prussia, the Austrian rocket brigades met their match against newly designed artillery pieces. Breech-loading cannon with rifled barrels and exploding warheads were far more effective weapons of war than the best rockets. Once again, rockets were relegated to peacetime uses.

Modern Rocketry Begins

In 1898, a Russian schoolteacher and scientist, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935), proposed the idea of space exploration. In a report he published in 1903, Tsiolkovsky suggested the use of liquid propellants for rockets in order to achieve greater range. Tsiolkovsky stated that the speed and range of a rocket were limited only by the exhaust velocity of escaping gases. For his ideas, careful research, and great vision, Tsiolkovsky has been called the father of modern astronautics.

|

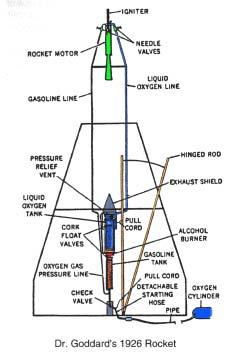

Early in the 20th century, an American scientist, Robert H. Goddard (1882-1945), conducted practical experiments in rocketry. He had become interested in a way of achieving higher altitudes than were possible for lighter-than-air balloons. He published a pamphlet in 1919 entitled A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes. It was a mathematical analysis of what is today called the meteorological sounding rocket.

Mail

Mail Share

Share Print

Print

Video

Video

2009 China Central Television. All Rights Reserved

2009 China Central Television. All Rights Reserved