This weekend, the Getty Center, one of the most famous museums in the U.S., will open a new exhibit years in the making. “The Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road” features incredible full-size replicas of ancient painted caves found in China. The project is a joint effort between Getty Conservation Institute and Dunhuang Academy.

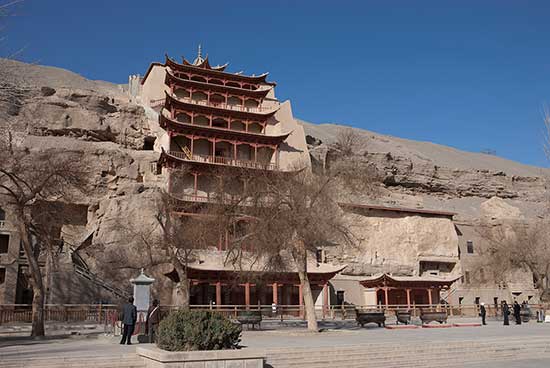

The nine-story temple (Cave 96) houses a colossal Tang dynasty Buddha statue some thirty-three meters high. Mogao Caves, Dunhuang, China. Dunhuang Academy.

In the Northwestern province of Gansu, China lies the Dunhuang Oasis, once a strategic point along the Silk Road and home to the spectacular Mogao cave temples. Nearly 500 grottoes feature Buddhist wall paintings and statues from the 4th to the 14th century.

For most people, visiting this remote UNESCO World Heritage Site is not likely, but thanks to a long term project between Dunhuang Academy and the Getty Conservation Institute, or GCI, replicas of three Mogao caves are now in Los Angeles’s Getty Center for a special exhibit.

All the caves are exact copies of how they look now in Dunhuang with all the wear and tear from the elements, natural disasters and even archaeological pillaging. These two sections are at a museum at Harvard University.

Neville Agnew of GCI has worked on the Mogao conservation project for 28 years. He is familiar with every hand-painted inch of every cave and all the colorful stories.

“Well, they’re brought to justice and they’re blinded heir eyes are put out,” Agnew said.

Professor Fan Jinshi, of Dunhuang Academy, has been preserving and managing the Mogao grottos since 1963. Her team of trained artisans in Dunhuang painstakingly copied the cave paintings for years using the same, original methods from centuries ago.

“To be able to bring such a large exhibition to the U.S. for the first time I'm so excited and happy to see this all finally happen,” Professor Fan said.

The Getty Conservation Institute began working with Dunhuang Academy in 1989. First focusing on research and site stabilization and then conservation techniques to help stem further deterioration.

“We’ve taken some of that knowledge, and now we’re applying it to work we’re doing in Egypt at King Tut’s tomb. So what we’re trying to do with what we accomplish in one place is to share that knowledge and that understanding in many, many places,” said Tim Whalen, director of Getty Conservation Institute.